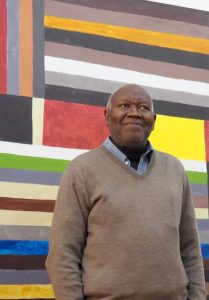

With a heavy heart, I deeply regret to announce the unfortunate passing of a dear friend, brother and colleague, (Dr.) Atta Kwami. Atta, as I called him, died on the afternoon of October 6, 2021 after succumbing to a fight with cancer.

He recently turned 65, on September 14, and we all wished him happiness, good health and long life. Even though I had learnt of the terminal nature of Atta’s illness, his positive response to all the birthday felicitations on social media was so heart-warming, little did I think he would leave us so soon. This makes his transition rather shocking and painful. He was hoping to have visited his dear homeland, Ghana, at least, for the last time, but it was never to be.

Atta Kwami was one of Ghana’s most internationally distinguished artists. He was not only a passionate and consummate painter, and installation artist, he was also an Art Historian, and wrote quite extensively on Ghanaian contemporary art. In 2013, he published the seminal book, “Kumasi Realism – An African Modernism, 1951 – 2007, which documented the development of contemporary art in Kumasi – Ghana’s second biggest city after Accra, the capital – where Kwami spent many years as student and lecturer at Ghana’s premier College of Art of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST)

As a painter, Kwami had always had an experimental bent, right from the beginning. He started off as an Abstract Expressionist, working in the vein of the Action Painters, sticking pans and other detritus from the environment into his paintings. Shown in Ghana, they were quite a novelty on the largely conservative art terrain, where most artists at the time worked in the representational and figurative mode, intently capturing the genre of the day. His annual exhibitions he jointly held with the Painter/ Sculptor Kofi Setordji and the Painter Emmanuel Anku-Golloh at the Goethe Institute in Accra were very much looked up to with excitement. After many years, Kwami transformed from his earlier Ab Ex style of painting into a Geometric Lyrical Abstractionist, working with loosely constructed grids and strident but sonorous colors. His canvases vibrate with so much energy. In later years he translated these gridded paintings onto free-standing sculptures – monumental arcades, constructed with plywood, and kioks, which are ubiquitous in the Ghanaian urban landscape. While the gridded paintings on the arcades and kioks were hard-edged, his paintings on canvas remained loosely gridded.

Kwami established in Kumasi, Ghana the SaNsA International Artists Workshop, a wing of the International Triangle Artists Workshop (a brainchild of the British Master Sculptor Sir Anthony Caro), which brought local and international artists together for a couple of weeks, to work and exhibit their art. SaNsA in Ghana ran three iterations, from 2004 to 2009.

Kwami specially invited me to be part of the last installment of SaNsA in 2009, with my participation fee, boarding and lodging fully covered by the organization. Unfortunately, I couldn’t honor the invitation, because I had just lost my father and I was saddled with organizing his funeral. Later, in a phone conversation, Kwami told me what I had missed, that the event was immensely successful. “It was like an international biennale,” he excitedly chatted.

While teaching at KNUST, Kwami set up an avant-garde art journal, BAMBOLSE, with the assistance of two of his protégés, who were students at the Art College, the Painter and Musician Henri (Papa) Asare-Baah and the Painter George Afedzi Hughes. BAMBOLSE ran for a few years.

It is significant to mention here a distinguished art teacher of Kwami, who taught him in secondary school, at the prestigious Achimota School, in Accra, then, also, at KNUST Art College – preeminent Ghanaian Painter (Prof.) Ato Delaquis. Interestingly, they later became colleague teachers at the Art College, good friends and lived a few meters apart on the same street.

Kwami himself was born into an artistic family, his father, Robert Kwami, a music teacher and the mother, a prominent first generation Ghanaian contemporary artist, and teacher. She was Grace Kwami (nee Anku).

Kwami maintained studios between Loughborough, U. K. and Kumasi, Ghana.

Kwami and I participated in a number of major group exhibitions together, notable among them, (1): “West to West: Owusu-Ankomah and Friends,” 2013 at the State Gallery of Bremen, Bremen, Germany, which also featured Owusu-Ankomah himself, Bright Bimpong, Sokari Douglas Camp, Godfried Donkor, Romaould Hazoume, George Afedzi Hughes and Lawson Oyekan, and (2): “The Poetics of Cloth: African Textiles/Recent Art,” at the Grey Art Gallery, New York University, New York, U. S. A, 2008, featuring other African giants, El Anatsui, Samuel Cophie, Viye Diba, Sokari Douglas Camp, Group Bogolan Kasobane, Abdoulaye Konate, Rachid Koraichi, Grace Ndiritu, Nike Okundaye, Owusu-Ankomah, Yinka Shonibare,, Malick Sidibe, Nontsikelelo “Lelo” Valeko and Sue Williams.

Kwami’s work was exhibited all over the world and featured in many important publications on contemporary African art. They found their way also into major private collections and museum holdings in Africa, Europe and the U. S. A., including, Movenpick Ambassador Hotel, Accra, Ghana; Ghana National Museum, Accra, Ghana; Kenya National Museum, Nairobi, Kenya; The Smithsonian National Museum of African Art (SNaMAA), Washington, D. C., U. S. A.; Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey, U. S. A.; Metropolitan Museum and Brooklyn Museum, both in New York City, NY, U. S. A.; the V & A and the British Museums, London, U. K. . Earlier this year, 2021, Kwami deservingly won the 2021 Maria Lassing Foundation Prize, which had a 50,000 Euro (£42,000) component; an exhibition project with the Serpentine Galleries, London and a monograph publication in 2022.

Kwami was represented in the U. K. by the Beadsmore Gallery, London; in Switzerland by the Nicholas Krupp Gallery, Basel, and in the United States by the Howard Scott Gallery, Chelsea, New York. He had at least three solo shows with his New York gallery, Howard Scott, before it closed down a few years ago.

Two of some of Kwami’s monumental public sculptures, a twin arcade rendered in his usual hard-edge, gridded, colorful composition, and a small cluster of kioks, painted in a similar manner, were on display at the Folkestone Triennial 2021 from July 22 to November 2, 2021. The exhibition was on when Kwami sadly passed. The twin arcade was titled, “Atsiafu fe agbo nu,” in his native Ewe (Ghana) language, which literally translates to, “Gateways of the Sea,” The colorful kiosk, also titled in Ewe, “Dusiadu,” which translates to, “Every Town,” emphasizing the ubiquity of the kioks, which come in varied shapes and colors and are a constant presence along the roads iin the urban centers in most Sub-Saharan African countries, especially, in the artist’s own country, Ghana, as I intimated earlier. These works were specially commissioned for the Folkestone Triennial 2021, which is U. K.’s biggest urban outdoor contemporary art exhibition, in the Kent coastal town of Folkestone, a former seaport.

Kwami was a keen intellectual, very erudite, I must say. Apart from our art, we shared a common passion – a crazy, inveterate indulgence in profuse art literature, art history, libraries, books and writing. We would often discuss new books we were reading. Kwami was always very much abreast with new publications on art, especially, African art, and he would recommend a book or two to me. On one of his visits home from the U. K., he brought me a gift of the newly published catalog on El Salahi, accompanying his retrospective at the Tate Modern, London, which I appreciated very much. It has a special place in my library.

I do not know when Kwami joined ACASA (The Arts Council of the African Studies Association). As far as I could remember, he had always been a member of ACASA. He was already a member before the advent of the Internet in Ghana. He must have joined the association in the 1980s or early 1990s.

Being one of the longest standing living Ghanaian members of this august association, it was just appropriate the mantle fell on Atta Kwami to deliver the keynote address at the opening of the 17th ACASA Triennial Symposium on African Art, which took place in Accra, Ghana; at the verdant University of Ghana – Legon campus. This was the first time ACASA, obviously the biggest body in the world with its members specializing in the study and scholarship of African art, and the material and expressive cultures of the African continent, in its over-five-decades of existence was having its triennial conference on African soil.

From March through May 2010, Kwami was an artist-in-residence at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in Washington, D. C., which is strongly affiliated to ACASA, having won the second edition of the Philip Ravenhill Fellowship, the first having been won by the artist, writer, academic and fellow ACASA member, Dr. Tobenna Okwuosa. The Ravenhill Fellowship was awarded by the UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) Fowler Museum, another strong affiliate of ACASA, and instituted in memory of Philip Ravenhill, Chief Curator of the National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, (1987 – 97).

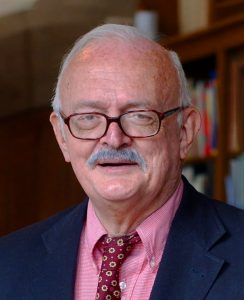

At the end of his residency at the National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, Atta Kwami was in conversation with the esteemed Art Historian, Prof. Sylvester Ogbechie of University of California, Santa Barbara; who is, also, the Founder and Editor of the journal, “Critical Interventions, ” and a long-standing member of ACASA. This was in the Fall of 2010, at the Fowler Museum and it was part of the museum’s public programming, “Fowler Outspoken Conversation.” The topic under conversation was, “Africa and Modernity.” The two gentlemen explored modernity and African art as embodied in university and local art practices in West Africa, specifically, Ghana.

Atta was a gentleman, in the truest sense of the word. He always had a calm disposition about him and would welcome you with a broad smile. He was always gracious in his manners, generous and humble.

Atta Kwami died in the U. K. His mortal remains was interred in a simple but colorful ceremony, attended by friends and family, at the Prestwold Natural Ground Cemetery, Loughborough, in Central U. K. on Friday, October 15.

Atta Kwami was survived by his dear artist spouse, Printmaker Pamela Clarkson-Kwami. My heartfelt condolences to Pamela, his numerous friends and family (home and abroad) and the Ghanaian art world. Ghana has, indeed, lost a rare gem of an artist and an intellectual!

Journey well, my brother. I wish you eternal rest in the bosom of the Lord, our Creator.

DAMIRAFA DUE!!!…

DAMIRAFA DUE!!!…

DAMIRAFA DUE!!!…

DUE NE AMENEHU!!!!!!!…..

By Rikki Wemega – Kwawu