In Memoriam: Ijeoma Uche-Okeke

Ijeoma Uche-Okeke passed on September 1, 2022. We will remember her forever.

Ijeoma was a dedicated leader in the arts and culture sector for over 15 years. In South Africa, she served as a Manager at the Visual Arts Network of South Africa and at Gallery MOMO, and as a Project Coordinator at !Kauru Contemporary Art Project where she managed a range of local, regional and international artistic programs. Up until her death, Ijeoma Loren Uche-Okeke was the Chief Executive Officer of the Asele Institute, a cultural institution founded by her late father, master artist and scholar, Uche Okeke, in Nimo, Anambra state, Nigeria in 1958. The Asele Institute houses an important repository and collection of contemporary African art. Ijeoma assumed her position at Asele in 2019 developing the organization’s board, exhibitions and programs. Her drive and determination in preserving her father’s legacy and championing African artists by further developing Asele into a global institution was groundbreaking. In 2019, she co-edited the re-launch of Uche Okeke’s “Art in Development – A Nigerian Perspective” published by iwalewabooks. She also co-curated a major exhibition at Iwalewahaus “We will now go to Kpaaza” featuring selected works of Uche Okeke, which opened in 2022.

In Memoriam: Yusuf Grillo (1934-2021)

We remember Yusuf Adebayo Cameron Grillo, who passed away on August 23, 2021 at the age of 86 after a brief illness. A foremost artist, administrator, and educator, he leaves behind an indelible imprint on the landscape of contemporary Nigerian art.

Born in the Brazilian Quarter of Lagos in 1934, Grillo had an early interest in art and mathematics in school. He continued these activities into his university education at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science, and Technology (now Ahmadu Bello University) in Zaria. While there, he and a group of fellow students including Uche Okeke, Bruce Onobrakpeya, Demas Nwoko, and Simon Okeke formed the Zaria Art Society in 1958. Art Society members challenged their Eurocentric education and sought to establish an artistic mode more fitting for a nation on the eve of its independence. They developed an artistic philosophy they called “Natural Synthesis,” which advocated merging indigenous Nigerian subject matter and forms with select European techniques.

Grillo took this synthesis as a foundation to develop a painting practice that presented Nigerian life through a palette of rich hues and fractalized compositions. He was a renowned colorist, and his canvases are often characterized by their different tonalities of blue. Grillo found inspiration for his artistic subject matter in people he knew, scenes he encountered on the streets of Lagos, Yoruba spiritual beliefs, and oriki. His artwork, for the most part, centered on the human figure and he is perhaps most well-known for his portrayals of Yoruba women and musicians. Indeed, these predominant themes reflected his compositional concerns. While Grillo greatly admired European Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, the influence of which can be seen in his thick brushstrokes and expressive use of color, he also seemed to have found equal inspiration in Yoruba dress and music. The linear and geometric qualities of the flowing folds of his figures’ garments often extended into the rest of the composition, and the layered angular divisions in his canvases imbued them with a certain rhythm.

Grillo would famously spend years creating his paintings. He worked on several works at once, stopping, starting, and returning to the canvases over long periods of time. In fact, he was in the habit of not signing his paintings because he never saw them as completed. For Grillo, the painting process involved a back-and-forth between the artist and the canvas that merged the conscious with the unconscious and unfolded organically. Rather than deeming a painting “finished,” he decided to move on only after he finally felt he could let go of it.

In addition to his painting practice, Grillo created stained glass pieces and a number of sculptural public artworks. The medium of stained glass particularly lent itself to Grillo’s interest in mathematics and the geometric division of his compositions. Perhaps his most well-known public artworks are his mosaic mural at Lagos’s City Hall and his cement murals at the Murtala Mohammed International Airport. With these works, Grillo contributed to the city he called home throughout his life.

Grillo has also been an important presence in the professionalization of the Nigerian art world. He was a founding member of the Nigerian Society of Artists (SNA) in 1963, and in 1964, he was elected the organization’s first president. Under his tenure, the SNA participated in yearly independence celebration exhibitions. He also brought the SNA into the UNESCO-affiliated International Association of Art, which led to opportunities for him and SNA representatives to travel and exhibit internationally.

Grillo received his post-graduate diploma in education in 1961 and also studied arts education at the University of Cambridge in 1966. His role as an educator has had a lasting impact on Nigerian art. He taught at Yaba College of Technology for decades, at times serving as Head of the Department of Art, Design & Printing and Rector for the entire institution until his retirement. Grillo was passionate about teaching his students the foundational methods of art-making as the building blocks to develop their own artistic language. Although he was a towering pillar in the Nigerian art world, he did not encourage followers. Instead, he pushed his students to move beyond his and his fellow pioneers’ influences to find their own visual modes and approaches. Today, the art gallery on campus bears his name.

Grillo was celebrated as one of Nigeria’s leading contemporary artists throughout his lifetime, receiving recognition through numerous honors and awards. These included first prize at the All African Competition in Painting in 1972, the laudatory retrospective “Master of Masters: Yusuf Grillo” at Nigeria’s National Gallery of Art in 2006, and becoming the namesake for the Yusuf Grillo Pavilion, an exhibition space in Ikorodu, Lagos that exhibits many of Nigeria’s foremost artists.

Grillo’s life and work leaves us with a lasting presence: his name is quite literally etched into the cultural infrastructure of Nigeria. His memory will be continued by his family, his students, his peers in the Nigerian art world, and those in the ACASA community who had the privilege to meet and know him.

Rebecca Wolff

In Memoriams: Robert Farris Thompson (1932-2021)

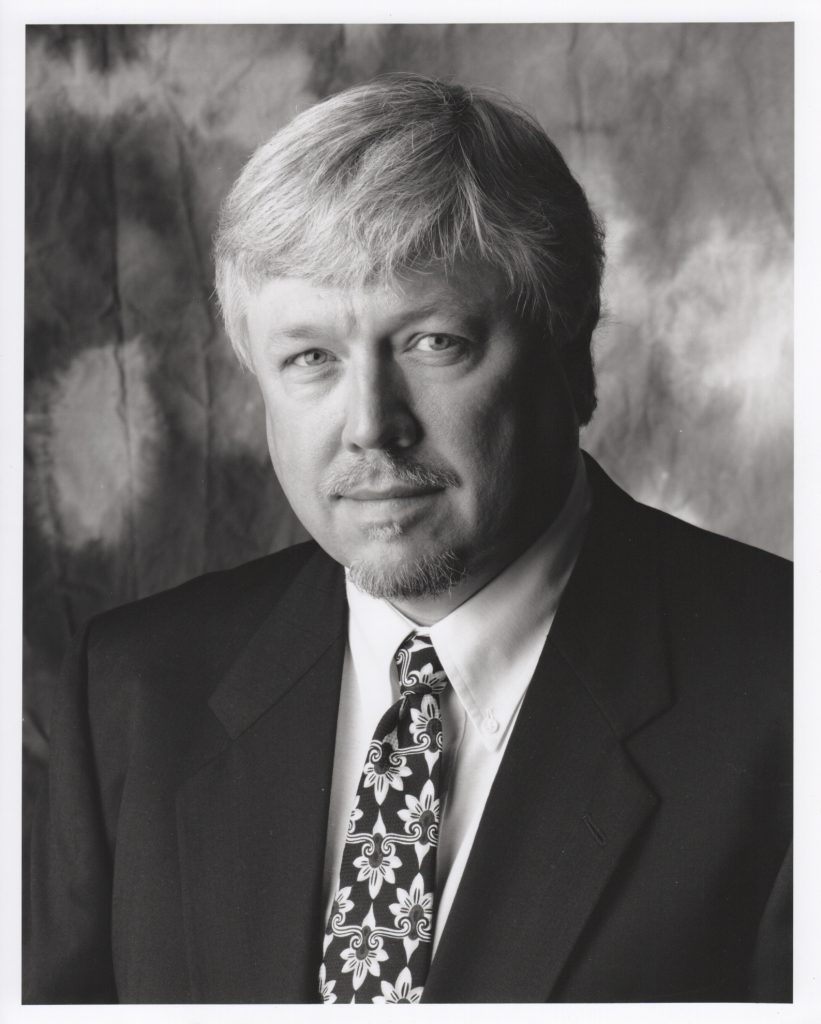

Robert Farris Thompson, born December 30, 1932, was the Colonel John Trumbull Professor of the History of Art, on the faculty since 1965, and Master of Timothy Dwight College, at Yale University, 1978 until 2010. He passed away on November 29, 2021, at 88 years of age.

Professor Robert Farris Thompson – “Who is this man,” I thought when I first met him. It was around 1974, and I was dutifully cataloguing slides at the Eliot Elisofon Archives, Museum of African Art, as a young master’s student, and new archivist. He rushed into the room, gasping for images of Africa, and awe-struck by everything he saw, exclaiming in Yoruba, complete with expletives, wild with enthusiasm, and finding gold mines of evidence everywhere. I was a student of dance and art, with pretensions of becoming an art historian, and a few years later, the head of my dance department, Shirley Wimmer, called me up with great excitement, saying she had just heard a lecture by Robert Farris Thompson, and knowing my desire to get into African art, she said “You have to go to Yale.”

Robert Farris Thompson was a legendary professor of the history of art in Africa and the African Diaspora in the Western Hemisphere and throughout the world. Yale University was his home throughout his adult life, and Thompson and Yale have been synonymous for thousands of Yale graduates for a half century. From Yale, he received his BA in 1955, his MA in 1961, and his PhD in 1965. He studied for the doctorate under Professor George Kubler, then a specialist in Spanish art. But his heart was in African American and Latin American culture. His dissertation fieldwork was conducted among the Yoruba in Nigeria because he wanted to find the sources of African American arts and culture. He began teaching in the History of Art in 1961, and was later honored as the Col. John Trumbull Professor of the History of Art. His undergraduate course, “From West Africa to the Black Americas: The Black Atlantic Visual Tradition,” was considered part of the tradition for any Yale College student. From 1978 to 2010 he served as Master of Timothy Dwight College, the longest run of any serving master. TD students revered him as “Master T,” and the College produced sweatsuits showing a caricature of Thompson as a muscular bodybuilder, with the word “ashe” – the Yoruba term for “inner power.”

Probably his most pivotal piece of writing was the article in which he explored “An Aesthetic of the Cool,” appearing in African Forum, in 1966. Thompson is known internationally for his continually groundbreaking publications, beginning with the catalogue for an exhibition at UCLA based upon his PhD dissertation, entitled Black Gods and Kings: Yoruba Art at UCLA (1971). In 1974, UCLA and the National Gallery of Art, sponsored an exhibition that revolutionized thinking about African art and culture, with a book entitled African Art in Motion: Icon and Act in the Collection of Katharine Coryton White. Again, for an exhibition at the National Gallery in 1981, he published, with Joseph Cornet, The Four Moments of the Sun: Kongo Art in Two Worlds. In 1984, drawing upon his decades of lecturing on the arts of Africa trans-Atlantic world, he published one of the most influential works on the continuity of African art in the new world, entitled Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy. His Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and the African Americas, in 1993, for the Museum for African Art, New York, accompanied the exhibition that traveled around the world to great acclaim as an examination of ensembles of sculpture never before considered by art historians.

Thompson was born to a wealthy El Paso, Texan, family, son of Dr. Robert Farris Thompson, a surgeon, and Virginia Hood Thompson, a patron of the arts, and received a patrician education attending secondary school at Phillips Academy Andover, in Massachusetts, before admission to Yale. But he was anything but orthodox, despite his tweed sport coats and penny loafers. As a “Yalie,” he would slip out of New Haven and go down to New York to the smoky Black jazz clubs, where he got to know all the early jazz greats. He started out, after getting his BA in 1955, traveling to Paris, with the hope of becoming a jazz player. He later championed such musicians as Tito Puente and Coltrane. His earliest article was on “Afro-Cuban dance and music,” published in 1958, followed by another in 1961 on “African Music.” He wrote a book on Tango, and his last teaching years were devoted to his course, “New York Mambo: Microcosm of Black Creativity.”

His art history was published in the traditional academic venues, but also in The Village Voice, The Fat Abbot, Rolling Stone, and Saturday Review. Among his many exhibitions, two of his most monumental were at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC: African Art in Motion, 1974; and The Four Moments of the Sun: Kongo Art in Two Worlds, 1981. He was recognized by the Arts Council of the African Studies Association with its “Leadership Award” in 1995. He was awarded the College Art Association’s inaugural “Distinguished Lifetime Achievement Award for Art Writing” in 2003, and was named CAA’s Distinguished Scholar in 2015. In 2007, Thompson was honored with the “Outstanding Contribution to Dance Research” award by the Congress on Research in Dance. In 2021, Thompson was awarded the honorary degree – his fourth Yale degree — Doctor of Humanities, by the President of Yale University. The College Art Association aptly described him as a “towering figure in the history of art, whose voice for diversity and cultural openness has made him a public intellectual of resounding importance.”

Long before “globalism” was even a word, he was preaching it in his classroom. The first day in class, the students were shown a slide of the world which Thompson zoomed in on until he reached Tokyo, Japan, and this was his springboard to upset all the preconceived notions about a bounded and traditional Africa. If he could find Africanisms in Japan, it was not such a leap to the Americas. He coined the term, “The Black Atlantic.” His forceful 1983 work, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy, was the culmination of his lectures at Yale, and was as much a praise song to African American culture as a tediously-researched, groundbreaking work of scholarship.

No one who ever sat through a Thompson lecture ever forgot it. It was an extravaganza of masterful drum playing, dance, song, and all the poetry and cadence of a southern preacher in the Black church. His performance never diminished — even when he was stuck in a little seminar room with three of us graduate students around a table, our jaws dropped to the floor. He would assign us readings in any language – You don’t read Dutch? — get a dictionary. He would punctuate his lectures with Haitian Creole, French, German, Hebrew, Italian, Kikongo, Portuguese, Spanish, Yoruba, and other languages, without translation. He once told me the secret to his success: “I am shameless.” His kiKongo wasn’t perfect, and he didn’t have a dancer’s body, but he never let that stop him from going full out to learn every tango and mambo dance step, every multimeter rhythm, every chant and praise song that he could. He didn’t care if you liked it. He liked it, and that was abundantly obvious as he reveled in all that he did.

Bob will be greatly missed by his dozens of Yale protégés now prominent in the fields of African and African American Art, thousands of Yale College graduates, and the world of lovers of African and African American music, dance, and art. A memorial service will be held in the Spring at Yale University.

— Frederick John Lamp, Yale University PhD, 1982; Retired Curator of African Art, Yale University Art Gallery, and Lecturer in Theater Studies and The History of Art, Yale University

In Remembrance of Robert Farris Thompson

I first met Robert Farris Thompson when I was a student at UCLA. He had come to campus to give a lecture for the opening of his Yoruba exhibition Black Gods and Kings. I got to help him set up his slides in the auditorium sound booth and all of a sudden he just started drumming on the counter. I started drumming along with him and next thing I knew he invited me on stage to drum with him in the middle of his talk. As he moved through his lecture he presented ideas and issues I rarely heard other art historians engage, and I was honestly in awe. Two Yoruba gentlemen were sitting in the front row, and they liked what he was saying too, nodding as he repeatedly made critical points. Of all the things that impressed me, what captured me most completely was his ability to demonstrate and bring to life the fundamental relevance of art to social life and human imagination. His talk was liberating.

Shortly thereafter I moved to New Haven and become one of his graduate students, and then I became a graduate assistant for his big African survey course. That was a transformative experience, not just for me but for the huge number of undergraduates who found themselves most fortunate to be taking such a class. He brought artists up from New York city to share their knowledge and experiences with us. He maintained a huge class bulletin board for the class that was mind boggling in its dense, rich, near chaotic presentation of words and images. He had a penetrating consciousness that virtually compelled you to think. As his student, he seemed to me a paradox: rigorous and demanding and very attuned to scholarly detail on the one hand, while simultaneously offering a freedom to explore that I found exhilarating. He made boundaries seem ripe with the potential to be challenged. He made you work, very hard. But he made you feel tremendous. I loved art history before I met Robert Farris Thompson. Being his student stretched the discipline’s worthiness for me in wonderful ways.

He has never stopped being all that to me. And more. Once after I finished my degree and was off teaching, I came back to New Haven to give a lecture. He was then the Master of Timothy Dwight College and known to all as Master T. We went to coffee and then he showed me his Master’s living quarters. There were several bedrooms, each with a double bed. And piled high on all of them were books and articles and notes and photographs; an enormous jumble of material, some quite rare and hard to find, with each bed’s treasures dedicated to a different research project. He kept vocabulary flash cards in a number of languages in his bathroom. He never stopped working with those flash cards or on each bed’s lush array of data. Put that together with the ways he totally submerged himself with people in the cultures where the arts he loved were made, and it is hardly a surprise that his research was spectacular, his writing evocative.

I very often think of RFT, and what he gave me. He made it clear, all the time, that you should understand the people whose art you study as full of sophisticated and complex ideas, rich practices and significant experiences, all worthy of our attention. His sense of humanity, his profound dedication, his ability to balance philosophy and practicality, his mind as fertile as minds can get: these qualities will always define my memories of a person I deeply cared for.

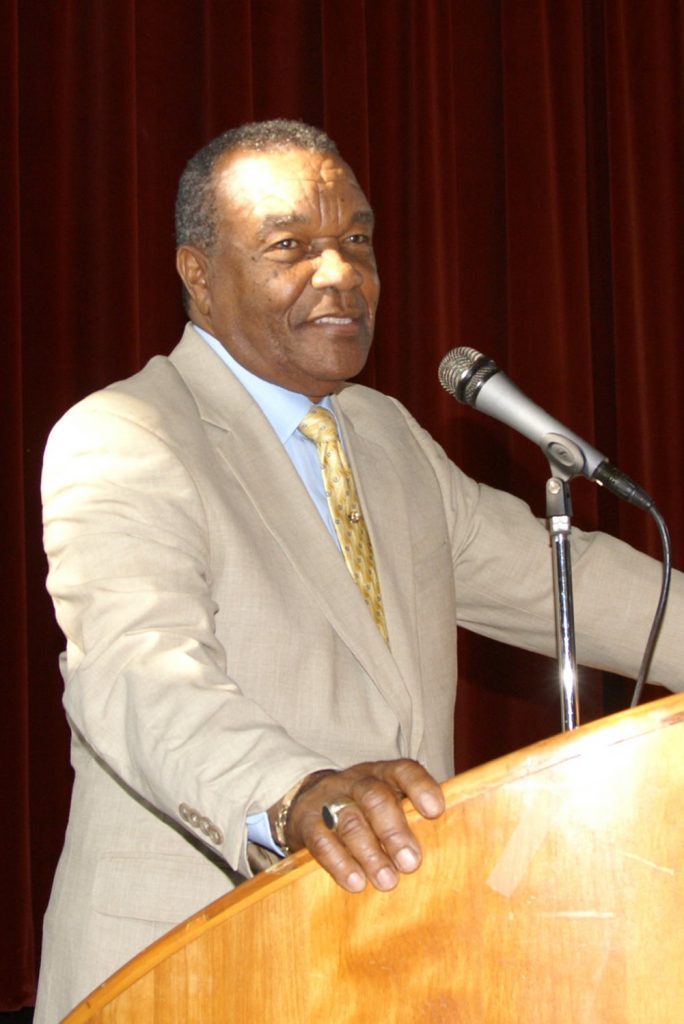

– Patrick McNaughton

Party at the ancestors’!

There will be music: a Big Band, Gwo Ka, and thumb pianos

There will be a toast with Guédé at the other high noon

Dancing with Egungun.

Party at the ancestors’!

There will be T-less Yalies

A table at Morey’s

They have been waiting for you.

High five, man! it’s cool, man…

We can hear the laughs from here, man

across the Kalunga

it’s Legba’s last trick, not yours.

Party at the ancestors’!

Altar’s ready, flashcards are ready,

Head, hand, spiritFaces up, pencils down

Let’s go, mambo.

–Cécile Fromont

William Fagaly, curator of NOMA’s African art collection, dies at 83

https://www.nola.com/news/article_d47d6172-b75d-11eb-825b-8fa598ea1fd7.html

In Memoriam: Ola Oloidi (1944-2020)

By Okechukwu Nwafor

In 1976 Ola Oloidi had registered to become a student of Frank Willet in art history of Northwestern University, United States. That same year, 1976, his father died suddenly. His father’s death altered his plans. He quickly returned home to Nigeria to console his widowed mother. In my interview with Oloidi in 2005, he noted, “When I came home after my father’s death, I accidentally saw an advert from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka and I quickly applied.” In his application, Oloidi said he emphasized his ideological orientation towards the humanistic in African art. Being one of the key ideological postures upon which the department at Nsukka fastened its teaching philosophies as at then, Oloidi made the list among the four applicants for the job. Uche Okeke, the then Head of Department, did not hide his preference for Oloidi in his statement: “This is the man I want, please I have to drag him.”

That was how Ola Oloidi came to the Department of Fine and Applied Arts at Nsukka. Although Oloidi had acknowledged the role Yusuf Grillo, a foremost artist of the Zaria Art Society, played in his career as an African Art Historian when he was at Yaba College of Technology in the 1960s, he owed his foray into contemporary African art to Uche Okeke. It was him who made Oloidi to recognize the problem of art historical studies in Nigeria. Oloidi said that the greatest challenge to the study of art history in Nigeria is lack of focus, problem of definition and understanding what we mean by art history. It was based on these understandings that Oloidi noted, “we are not teaching art history proper in Nigeria, sometimes we teach fugitive art history.” In fact, Oloidi believed that journalists wrote better art history than Nigerian art historians. In his attempt to separate art history from art theorizing, his well-founded methodology of African art history became intrinsically entrenched as an Nsukka tradition. Oloidi’s words, quite predictive and candid, has become a plausible sermon that his death has brought back to us once again.

Oloidi had obtained a Bachelor of Fine Arts and Master of Arts degrees at Howard University, Washington, DC in 1973 and 1974 respectively before returning to Nigeria after his father’s death. Worried by what he described as ‘Anthropological excesses’ in the teaching of African art history Oloidi made a timely intervention in the teaching curriculum of African art at Nsukka by downplaying the preponderance of primitivism which formed the rudimentary watchword of ‘proper’ African art history. He instead introduced contemporary African art. In this way, he not only brought a holistic perspective to the syllabus at Nsukka but also helped to shape the intellectual aspect of modern Nigerian art history starting from the late twentieth century. This must have also contributed in forming a generation of brilliant art historians that emerged from the Nsukka art school such as Olu Oguibe, Sylvester Ogbechie, Chika Okeke-Agulu, Krydz Ikwuemesi, Ugochukwu Smooth-Nzewi, myself, among many others. Indeed, the making of the Nsukka art school both in critical art historical scholarship and studio practice has been attributed to a number of factors of which Uche Okeke, El Anatsui, Obiora Udechukwu, Chike C. Aniakor and Oloidi played a key role.

Apart from his influential role in nurturing the abovementioned individuals, Oloidi deeply understood the meaning of African art history with a clear idea of how it should be taught. He brought this knowledge to full bear at the Nsukka School of Art. Olu Oguibe remarks, “I hope that I have in some little way justified Oloidi’s keen and selfless investment in training me to become a serious scholar and a decent human being.” Oguibe’s hopes, undoubtedly a sentiment that is driven by a deep sense of acknowledgement, may re-echo similar wishes by Oloidi’s former students of which I am one. I remember Oloidi’s classes as one of the most entertaining and illustrative on campus. In one of the lectures, he posed in a profile position to illustrate a Baule wooden figure to us. His profile pose, his long grey beard and slightly bent legs captured the essential characteristics of Baule figures. The exactitude of his mimic of Baule figure was a powerful lecture strategy that enabled most of us to identify Baule figures till date.

With an undefined preoccupation that came with the study of art history in the 1980s, Oloidi reinvigorated art history with a modernistic persuasion that centers on the biographical figure, a key ontological feature of art history essentialized as a preserve of the West before the 1990s. He achieved this with a most compelling and comprehensive scholarly investigation into the lives of pioneer artists in Nigeria such as Aina Onabolu and Akinola Lasekan. It is unfortunate that while many art historians have written on the works of these pioneer artists, Oloidi’s mimeographs remained largely obscure and unreferenced despite being the most primary and authentic sources of this scholarship. Indeed, Oloidi’s personal engagements and close encounters with Onabolu’s and Lasekan’s works and his personal banters with members of their families in the form of interviews, recorded archival documents, review of their works, among others, gives his scholarship its unrivalled primacy.

Oloidi’s comic disposition was uniquely his and an admirable attribute at the Nsukka campus. Outside the campus, a mixture of humor and academic devotion defined his personality throughout his lifetime. During one of our lectures, he teased us and said, ‘You all are unlucky not to have died.” It took us a while to digest the full import of the statement. This statement was a response to the excruciating experience occasioned by the infamous incursions of the military into governance, especially during the 1990s. Many Nigerian lecturers, including Oloidi and his colleagues in the art department at Nsukka, became victims of the military’s punitive misadventures in governance and witnessed the prevailing devastation in the education sector. Many migrated to the west, while Oloidi and a few others remained in Nigeria. Living through an endless cycle of catastrophe that characterized the Nigerian university education, even till his death, Oloidi remained a champion and a defender of an honest African art history. He joined the fragmented pieces of these histories, and retold them, successfully.

Oloidi retired as professor of African art history from the University of Nigeria in 2012 and was retained as an Emeritus. His excellent life will be missed, not just by his family but by the many students he mentored including more than 50 PhD students he supervised, many Masters and undergraduate students. He was the founder of the Art Historical Association of Nigeria (AHAN) and has been instrumental in the many symposiums and conferences organized under its auspices. In Nigeria, Oloidi would eventually become a compelling voice in important intellectual forums where Aina Onabolu scholarship demanded unmistakable elucidation. Research students travelled from all over the world to consult him on this area of Nigerian art history.

Oloidi is survived by his wife and two sons, having lost one of his sons some years back.

Okechukwu Nwafor is professor of art history at the Nnamdi Aziiwe University Awka and the author of the book, “Aso ebi: Dress, fashion, visual culture and urban cosmopolitanism in West Africa (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021).

In Memoriam: Doran H. Ross (1947-2020)

We remember Doran H. Ross, who passed away on September 16th after a long illness. Doran was a towering presence in our field of African art studies, not just for his size and charismatic personality but for the legacy he has left us as a prodigious scholar, curator, and leader as well as friend and mentor to so many. It was at California State University, Fresno, working on a double major in art history and psychology, that he was first introduced to African art and where that journey really began. He received his M.A. in art history at UCSB and went on to teach at various California institutions until his distinguished career at the Fowler Museum began in 1981 as Associate Director and Curator of Africa, Southeast Asia and Oceanic arts; he later became Deputy Director and Curator of African Collections, before becoming the first non-faculty full-time Director in 1996, a position he held until he retired in 2001. His first major exhibition at the Fowler (then the UCLA Museum of Cultural History) was The Arts of Ghana (1977), which he co-curated with Herbert M. Cole, and was accompanied by a comprehensive publication he co-authored. Doran was among the most important scholars of Ghanaian arts in the world—many would argue the foremost—with research interests that centered on the royal and military arts of the Akan peoples, especially their dress, adornment, and regalia. Among his Akan publication highlights are Akan Gold from the Glassell Collection (2002); Royal Arts of the Akan: West African Gold in Museum Liaunig (2009); Art, Honor and Ridicule: Fante Asafo Flags from Southern Ghana (2017) with Silvia Forni; and Akan Transformations: Problems in Ghanaian Art History (1983), which he edited. Doran would fight anyone who claimed that any other African culture compared with that of Akan-speakers of Ghana.

Doran was largely responsible for setting the standard for the Fowler’s highly researched, contextualized, and multi-media exhibitions of global arts, always paired with a scholarly volume, a paradigm that continues to this day. He was firmly committed to a team approach for exhibition development, believing that exhibitions benefitted from diverse perspectives beyond those of the erudite scholar—a methodology then considered novel, but one he saw as essential. Among the many highlights of his tenure were his contributions to getting the new Fowler Museum facility designed and built in 1992. He signaled the new institution’s ambition and vision with four simultaneous inaugural exhibitions (each with its book), including Elephant! The Animal and its Ivory in African Culture, which he curated.

Drawing on his huge reservoir of energy, Doran oversaw many other projects: he managed and/or curated some 38 African and African-American exhibitions that were shown at 30 different venues nationally. For example, his tenacity in spearheading the Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou project (1995), co-curated by Donald J. Cosentino and Marilyn Houlberg, resulted in one of the Fowler’s most memorable exhibitions and publications. Doran curated the important community-based project, Wrapped in Pride: Ghanaian Kente and African-American Identity (1991), an initiative that involved a year-long African art and field collecting course he co-taught with the Fowler’s Director of Education Betsy Quick at Crenshaw High School. A smaller version of this exhibition, initiated and funded by NEH on the Road and co-organized with Quick, traveled to 35 community venues around the country. Over his long term at the Museum, Doran oversaw the acquisition of thousands of objects into its permanent collections. His years at the Fowler were also a time when the Museum’s national reputation as an innovator in the development of exhibitions, the engagement of community advisors, and the production of multi-author publications was established with authority. Many Fowler projects were funded by the NEH and it was Doran who set the stage for the Museum’s long and successful record of receiving major grants from this key federal agency. During his years at UCLA he also taught a three-quarter Museum Studies course, inspiring students to seek museum careers while also mentoring graduate students at UCLA and elsewhere who benefitted from his wisdom, experience, and generosity. Because he felt such gratitude to his mentor and friend Skip Cole for inviting him as a graduate student to contribute to The Arts of Ghana, he went out of his way throughout his career to assist and advise students, and to create opportunities for them to publish their research. Doran served as an editor of the UCLA journal African Arts from 1988-2015, and published in it 47 articles, reviews, First Words, In Memoria, and Portfolios from 1974–2014.

Were that not enough, Doran also guest curated numerous exhibitions both nationally and internationally, working with large and small institutions; and consulted on collections building, film projects, self-study institutional initiatives, federal grant reviews, and museum studies programs. Over a span of several years, he also worked closely with two important collections of Akan gold at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and Museum Liaunig in Austria.

As a great proponent of research and exhibitions on global textiles, he also was co-editor of Textile: the Journal of Cloth and Culture from 2002 to 2012 and editor ofvolume 1 (Africa), The Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion (2010), both with Joanne B. Eicher. Doran was especially proud of the National Museum of Mali/UCLA Museum of Cultural History Joint Textile Collection and Documentation Project (1986–1992); while building collections for both institutions, he mandated that when questions of quality arose, the better example would be reserved for the National Museum of Mali. Always, Africa first.

Beyond Doran’s direct responsibilities associated with UCLA and Fowler projects, he was extremely committed to helping institutions and individuals in Africa. From 1974 to his last trip in 2014, he made 37 research and development trips to 18 African countries. Following the joint collection project with the National Museum of Mali, he served on the Board of the West African Museums Project (1993–2000), a policy and programmatic initiative to which he was deeply committed. As well, he served on the Selection Committee of the SSRC African Archives and Museums Project (1991–1996), was a member of the Arts and Artifacts Indemnity Advisory Panel of the NEA (1996–1999) and of the Advisory Committee of the Getty Leadership Institute (2000–2003).

Somehow, between writing and curating, building collections and consulting, he found time to be a lifelong student of film (his library numbered some 3000 DVDs) and music, most especially western Classical music, American jazz, and tradition-based and contemporary African music. Name a composer, a particular arrangement, or an obscure artist and undoubtedly one would find it in his library of 5000 meticulously catalogued CDs.

Doran’s participation in and promotion of ACASA is the stuff of legend. He joined the Board in 1984 and served as Secretary/Treasurer (1984-87), was Program Chair for the 7th Triennial in 1986, became President in 1987-1989, received the Arnold Rubin Book award in 2001 for Wrapped in Pride, served on the Rubin Book Award and Leadership Award Committees, and received the ACASA Leadership Award in 2011. His support of ACASA never waned and he attended every Triennial Symposium from Washington, D.C. in 1977 to Brooklyn in 2014.

In recent years, Fowler staff have been working with Doran on two exhibitions of Ghanaian art well represented in its collections: Art, Honor, and Ridicule: Fante Asafo Flags from Southern Ghana (an exhibition that opened at the ROM in 2017 and was co-curated with Silvia Forni) and the paintings of Kwame Akoto (a.k.a. Almighty God). They will be presented to honor Doran and his remarkable legacy of service to the Fowler and UCLA.

Doran Ross lived life to his fullest and his generosity of spirit knew no bounds. Just as his career was one of intense engagement and productivity, so too did he lavish his warm, teasing affection and robust sense of humor on his many friends near and far. His wordsmithing delights found joy in puns of all varieties, and the occasional pause in conversation signaled an always-hilarious play on words. He will be greatly missed by so many who loved him. He is survived by his sister Diane and by Betsy Quick, his partner of some 20 years.

I thank Suzanne Gott for sharing these lines from a fitting Akan song of mourning recorded by the late great Ghanaian ethnomusicologist Kwabena Nketia:

“The mighty tree with big branches laden with fruit. When children come to you, they find something to eat.”

– Marla Berns and Betsy Quick

The Doran H. Ross Fund for African Exhibitions has been established at the Fowler Museum to honor Doran. For information about donations, please contact Kris Lewis, Director of Development, at Krislewis@arts.ucla.edu

In Memoriam Santu Mofokeng (1956-2020) – a Visual Poet who Danced with Reality

Image courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

by Paul Weinberg

Santu Mofokeng’s sad and untimely passing brings with it a large and extraordinary legacy. For the last number of years, he had been suffering from progressive supranuclear palsy, a rare brain disorder which left him paralysed and in the care of his family, rendering him a bystander to a world in which he was so intimately connected to, as a photographer.

In paying tribute to him, Candice Jansen, director of the archival program at the Market Photo Workshop, said, “Santu Mofokeng has left us with an appetite for curiosity and food for thought for generations to come.” Santu was far more than a photographer. More aptly expressed by his son Kano at his memorial, “he saw more than what he looked at.” He was an incisive thinker who playfully and imaginatively danced with words and ideas around images. Santu like many black photographers who went on to become professionals, began working as a street photographer from an early age. He was given his first camera by his sister, while still at school. He joined the collective agency Afrapix, I was part of, in 1985. Until then, he had been working for the Beeld Afrikaans-speaking newspaper, as a darkroom assistant. It was a paying job but a tough one for such an expansive and creative spirit. In retrospect, we were a source of liberation for him.

As a rawdy collective of hippies, rads, strays, waifs, alternatives, and creatives, caught up in a moment in history, we shared a common vision to do whatever we could with and without our cameras, to bring down the oppressive system of the time. So it goes without saying, Santu fitted in perfectly. He became a much loved and highly respected member of the family. Santu himself later described Afrapix as a, “home that provided me with money to buy a camera and film in order to document Soweto and the rising discontent in the townships.”

One Friday afternoon Santu and I were sitting in the Afrapix office, then based in Khotso House, the headquarters of the South African Council of Churches, and the epicenter of human rights and activist organizations, chewing the fat. Santu is exactly the same age as me and by then we had become close friends, through the route of many arguments, debates and a lot of humor. It dawned on us that while we shared so much in common, we were about to leave to our different homes, defined by the political circumstances around us, divided by segregation and apartheid. It spawned the project Going Home, where for many years, Santu focused his lens on Soweto and I, on my home town, Pietermaritzburg. Soweto, where he was born and bred, continued to be for him, throughout his career, “the litmus that I use in order to survey or navigate my way through the world.”Santu went on to produce seminal work that took South African photography to new heights – Train Churches, The Bloemhof series, Chasing Shadows amongst others. He once said photography for him was like an autobiography. To the lives of ordinary black South Africans, he brought poetry, lyricism, compassion, intimate fragility and a profound sense of humanity in a time of great inhumanity. He did this in a period when South Africa made world headlines for almost a decade. He wasn’t interested in head counts or the news events of the day or being part of the photojournalist wave that most of us were caught up in then. His passion was to reflect the lives of his people and the communities with whom he shared a common journey.

In doing so Santu’s work will be remembered for his extraordinary insights and beauty he was able to advance and immortalize through his photographs. He was an insider who captured his subjects with great sensitivity, dignity, respect and perspicacity, mostly in his preferred medium, gritty and grainy black and white. Reality was his canvas on which he painted in light and shadow. His work defies easy categorization, and a semiotic shorthand that people usually apply in trying to understand the dominant styles and approaches to photography in South Africa – be it documentary, fine art or a hybrid version of the two. Santu worked in areas that became socio-economic and political clichés but he deftly traversed these boundaries in his inimitable rebellious way, allowing his camera to gravitate to the edges of life, to draw on the depths of reality and to entice the unexpected. In 2013 Santu and photo curator, Joshua Chuang, began selecting from the 32 000 digitsed images in his image archive. This culminated in the German photo-book publisher Steidl producing 18 stories of Santu’s life’s work (1986-2014), under the series title, Santu Mofokeng: Stories. This apexes a prolific career of forty years which includes more than 25 solo exhibitions, two traveling retrospectives, and featured appearances in a number of Biennales as well as the prestigious Documenta 11, in 2002 curated by Okwui Enwezor.

This is Santu’s gift to the country, the continent and the world. These powerfully searing and engaging images will live on as the Mofokeng corpus. For those who wish to continue exploring, understanding and unpacking this complex, creative, and at times enigmatic archive, they will become the fuel for our imagination, re-imagination and consciousness. But it is best I leave the last words to Santu who in his typically provocative and unsettling way, left us with some thoughts and meditations on the topics of archive and memory. In contextualizing his last body of work called Graves, from an essay called Ancestors Fearing the Shadows, he wrote, “The Chinese say that our body is a memory of our ancestors. This is an ominous proposition because apartheid is an impossible ancestor – inappropriate and unsuitable. Whenever we come under threat, we remember who we are and where we come from and we respond accordingly. The word remember needs elaboration. Remember is the process by which we restore to the body, forgotten memories. The body in this case is the landscape on whose skin and belly histories and myths are projected which is central to forging national identity. When I see turbulence, my sister sees a snake. As a photographer I hunt for things ephemeral such as shadows in order to create images. Interpretation I leave to the beholder.”

(Santu Mofokeng, “GRAVES 2012”, MAKER, Johannesburg, 2015)

Paul Weinberg is a photographer, curator, and research fellow at the South African Research Chair in South African Art and Visual Culture, FADA, University of Johannesburg.

In Memoriam David C. Driskell (1931 – 2020)

By Christa Clarke

We mark the passing of Dr. David C. Driskell on April 1, 2020 with profound sadness as well as enormous gratitude for his myriad contributions over the course of a career that spanned nearly seven decades. He is remembered as an artist, educator, art historian, curator and collector as well as a dedicated gardener, an inventive cook, and above all, a man devoted to his family. David helped shape and grow the field of African American art history and leaves a legacy through not only his own art and scholarship but also the generations of students he has mentored.

I was fortunate to be one of those students, having had the opportunity to study under David while pursuing my Ph.D. at the University of Maryland beginning in 1989. Though my field was African art history (and my primary advisor, Dr. Ekpo Eyo), my research interests focused on the reception of African art in the United States. David took me under his wing, generously sharing insights based on first-hand acquaintance and work with Harlem Renaissance-era legends such as Alain Locke and Aaron Douglas as well as his own experiences teaching and traveling in West Africa. Sitting with David in his art-filled, sun-soaked home as he shared his knowledge and insights was not only a thrilling walk through art history but a nurturing and empowering experience for a young graduate student.

Born in Eatonton, Georgia, on June 7, 1931, David found his calling as a young art student at Howard University. In 1949, he hopped on a bus to Washington DC and showed up at Howard, weeks into the fall semester and without having submitted an application. His tenacity paid off and he soon found himself studying under the pioneering artist/scholar James A. Porter and artists Lois Mailou Jones and Morris Louis. After graduation, David spent the early part of his career teaching at HBCUs, including Talladega College, Howard University and Fisk University, while also earning an MFA from Catholic University. He was appointed professor at University of Maryland in 1977, one year after he organized the landmark exhibition, “Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750-1950” for LACMA. David taught at Maryland for over twenty years and was named Distinguished University Professor in 1995, then Emeritus after his retirement in 1998. In 2001, the University established the David C. Driskell Center for the Study of Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora.

As an artist, David’s work continually straddled Africa and America, as art historian Julie McGee has observed in her 2006 monograph, David C. Driskell: Artist and Scholar. David first traveled to the continent in December 1969, visiting Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, and Ghana before heading to Nigeria to teach a January term at the University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University), just as the Biafran war was coming to a close. His experiences there, which included meeting artists in Osogbo and Benin city, visiting archaeological digs, and an audience with Oba Akenzua II, were inspiring and also reinforced for David his American-ness. As he later relayed to McGee, “I would simply say that I think part of the message that I desire to communicate in my art is that I am a Black American. I have experienced the haunting shadow of an African past without knowing its full richness.”

David’s gracious and unassuming character belied his many achievements. Among them are 7 books and 40 exhibition catalogues on African American art, 13 honorary doctoral degrees and 3 Rockefeller Foundation fellowships. David received the National Humanities Medal from President Clinton in 2000 and was inducted into the American Academy of Arts & Sciences in 2018. His art is seen in institutions throughout the United States, from stained glass windows at Talladega College to the powerful painting, Behold Thy Son, at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. And David’s many “firsts” include chairing the first panel devoted to African American art at CAA in 1970 and, 25 years later, selecting the first painting by an African American artist to be permanently displayed in the White House.

In the 21st century, David saw the growing impact of his pioneering efforts to foreground the work of African American artists in American culture and art history. He paved the way for many scholars, artists and curators, including the recipients of the Driskell Center’s book award and of the High Museum’s annual Driskell prize established in 2005 for contributions to African American Art, and for the organizers of blockbuster exhibitions such as the Tate Modern’s “Soul of a Nation,” and the Quai Branly’s “The Color Line,” both of which opened in 2017. I recall last summer how David wrote me in eager anticipation of a visit that day – his birthday — to Martin Puryear’s triumphant installation in the US Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. David needed to bear witness to and celebrate all of these achievements, while continuing to share his own considerable knowledge and experience, and literally traveled around the world to do so.

For those of us fortunate to have been welcomed into David’s orbit – and there are many – an added benefit of his warm embrace was that it included his family. As we mourn the passing of a truly extraordinary man, our thoughts are with his loving wife of 68 years, Thelma, his two daughters, Daviryne and Daphne, and his five grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Contributions in David’s memory may be made to support the work of the David C. Driskell Center at the University of Maryland: http://www.driskellcenter.umd.edu/

In memoriam: Nancy Ingram Nooter

Nancy Ingram Nooter, 92, noted scholar, collector, and teacher of African and Native American arts, died peacefully at her home in Washington on February 4, 2020. She is survived by Robert H. Nooter, her spouse of 72 years, and four of their five children and their families, having been predeceased in 2018 by their daughter Mary “Polly” Nooter Roberts.

The Nooters moved to St. Louis after their marriage, and later lived in Uruguay, Liberia, Tanzania, and Washington, DC, through Bob’s celebrated careers with the United States Agency for International Development and The World Bank. Nancy held a BA and an MA in Cultural Anthropology from George Washington University. She conducted field research in Kenya, the Sudan, and Tanzania on arts and architecture of the Swahili Coast, prehistoric rock paintings, and the carved doors of Zanzibar. While working at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art (NMAfA) in the 1980s, Nancy curated exhibitions, contributed to catalogues and display captions, helped organize the first docent program and establish the Summer Institute for young African Art Scholars and Instructors. She also taught classes on African art histories at American and Georgetown Universities and at the Smithsonian Institution. Nancy and the late NMAfA founder/director, Warren Robbins, co-authored “African Art in American Collections” in 1989, which remains the most comprehensive compendium on the subject.

Over the years, the Nooters made significant gifts of African and American Indian artworks to NMAfA, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts of Richmond, and the Walters Art Museum of Baltimore. Nancy also studied painting with Gene Davis in Washington and Fred Conway in St. Louis, Missouri. Her works have been exhibited at the Franz Bader Gallery in Washington, the Museum of Fine Arts in Little Rock, Ark. and many are owned by collectors in the U.S., Europe, West Africa and South America. Nancy served on the Board of ACASA and was a member of the Society of Women Geographers and the Cosmos Club of Washington DC.

Nancy Nooter’s grace, generosity, wit, and wisdom will continue to inspire family, friends, and admirers the world around. Her family asks that anyone interested in making a denotion in her memory to please consider doing so to her beloved National Museum of African Art.

In Memoriam: Sidney Littlefield Kasfir (1939-2019)

ACASA is extremely sad to pass on the news that Sidney Littlefield Kasfir, the renowned art historian and recipient of an ACASA Leadership Award in 2017, passed away in Kenya on 29 December 2019. We invited three people very close to her to write their personal obituaries:

Remembering Sidney Littlefield Kasfir

by Margaret Nagawa

While Transition journal’s pages made Kampala the center of newly independent Africa’s literary, political and artistic discourse, Nommo Gallery was the physical space where artists, writers, expatriates and the political elite mingled. Sidney’s curatorial work mediated the worlds of Makerere Art School, other departments in Makerere University, artists whose practice developed outside the art school, artisans in Katwe whose metalwork was rooted in responsibilities to Buganda kingdom, and political leaders. Her scholarly work linked Kampala to a readership in other art worlds. Unfortunately, the wars that ravaged Uganda into the mid-1980s suppressed open discourse and murdered real and imagined dissidents. This political unrest also affected the striving art scene in Kampala. Many artists were killed or went into exile, and art friends from abroad stayed away.Sidney was an active member of the Kampala art community before and after the wars and engaged in studio visits, curating, teaching and writing for local and international audiences. From the 1990s, Sidney regularly returned to Uganda to conduct research, attend art events like the Kampala Contemporary Art Festival (KLA Art 014), and work as a visiting scholar at the Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Arts. She would meet with old friends and visit artists’ studios like those of Rose Namubiru Kirumira and Maria Naita. Many of these encounters and studio conversations materialized in her publications about the country’s troubled history and vibrant art activities. During Seven Hills, the second Kampala Art Biennale in September 2016, Sidney gave a paper at the public symposium (Hi)Stories of Exhibition Making, 1960 – 1990. She spoke about some of the exhibitions she organized at Nommo Gallery discussing the artists Richard Ndabagoye, Jak Katarikawe and Francis Nnaggenda who also attended the symposium. Since 2016 she also worked as a member of Start Journal’s editorial team alongside George Kyeyune, Angelo Kakande, Jantien Zuurbier and myself. We miss her insightfulness and uncompromising stance on standards.

Sidney was a colleague, friend and mentor. She encouraged my writing and supported my pursuit of graduate studies at Emory University. On her visit to Atlanta in the summer of 2019, she joined my family for sumbusa and dinner. She loved our long-haired Shepherd and shared photos with her husband Kirati Lenaronkoito, who also loves dogs. We watched the Democratic Party presidential debates that evening and wondered which candidate would emerge to stand against Donald Trump. Sidney did not live to see that happen. Although her body rests in Malalal, Kenya, a home on the farm she dearly loved, I regard her writing as her heir that continues her legacy and keeps her generous and loving spirit alive.

With Gratitude for Sidney as Mentor

by Jessica Stephenson (Associate Professor of Art History and Interim Associate Dean Kennesaw State University)

In 1989, while in my second year as an anthropology and art history undergraduate student at the University of Witwatersrand, South Africa, I read Sidney Kasfir’s seminal article, “One Tribe, One Style?” It was a lifechanging read. Sidney’s ahead-of-its-time, paradigm-shifting thinking informed a paper I then wrote, a re-reading of Ndebele painted murals and beadwork, that won me the Standard Bank Group Foundation for African Art Scholarship Award in 1990, setting me on a course towards graduate school. By the time I was applying to programs Sidney had just published the “African Art and Authenticity: A Text with a Shadow” article, another critical influence that validated my decision to study commodification and rural art workshops in Southern Africa. I moved from one hemisphere to another to study big picture art history with her that just so happened to play out through application to African art.

Graduate work with Sidney was a stimulating and challenging ride, I think my colleagues, her students, Delinda Collier, Olubukola Gbadegesin, Jessica Gershultz, Amanda Hellman, Peri Klemm, Elizabeth Morton, Ugochukwu-Smooth Nzewi, Chika Okeke-Agulu, Amanda Rogers and Sunanda Sanyal, not to mention the numerous others who took coursework with her, would agree. Her mentorship was much like her writing: unconventional, sometimes circuitous, and richly exploratory. Seminars with Sidney would often headed down unexpected paths (a reflection of her creative range), so much so that it might be days, weeks or even months before one grasped the fullness of those conversations.

While other mentors eschewed curatorial work as an end-goal after graduate school, Sidney championed it, recognizing its central role in shifting academic and public discourse in the arts. She crafted many a curatorial opportunity for each of us so we could put theory into practice, make connections, and gain exposure. We were challenged to dive deep, to publish, present and curate right off the bat (as a second-year graduate student presenting for the first time at CAA, I was truly terrified), but since she pushed us to hone our professional skills early on, all her students were quick to successfully launch post-graduate careers within the African art field, a fact that she was most proud of. While she mothered her students, lavishing us with many a boisterous and delicious dinner at her home, there was no hand holding in the seminar room: “asking significant questions is the most critical skill for academia,” she would say. In a sense, she treated us, her students, as equals. Thus, in her characteristically generous manner, Sidney shared with all her students the Lifetime Achievement Award bestowed at the 2017 ACASA Triennial Conference. In so doing, she calls each of us to continue her lifelong love for inquiry.

Sidney remained in contact with me since retiring many years ago. I’d meet her each summer in Atlanta at a local Indian restaurant (she loved Indian food!). Our conversations centered on news of her students and her life and family in Kenya. She spoke of the certain hardships there, but through the challenges the clear love and belonging she felt was clear. After sharing tales of cattle raids and the effects of ongoing drought in Kenya she would drive off in her old hunter green Jaguar, so authentically Sidney, a unique character, so comfortable moving between, or more correctly, connecting, worlds, in life and in scholarship.

Photograph: Sidney Kasfir reading acceptance speech upon receiving the Lifetime Achievement Award, ACASA Triennial Conference, 2017, Accra, Ghana. She is accompanied by some of her former graduate students: (left to right): Peri Klemm, Chika Okeke-Agulu, Olubukola Gbadegesin, Smooth Nzewi, Delinda Collier, Amanda Hellman and Jessica Stephenson.

Photograph care of ACASA Facebook website.

For Sidney

Till Förster (Chair of Anthropology, University of Basel)

Long before I met Sidney, her work was a steady and reliable companion. Since my time as a PhD student in the early and mid-1980s, I read many of her articles and a little later the book which she edited after an Oxford symposium on West African masks and cultural systems. In particular her remarks on the interaction of play and ritual in masking performances were central to what I had observed in other parts of West Africa – and I am convinced, they still hold today.

I met Sidney finally at the ACASA Triennial Symposium on African Art 2001 in St. Thomas, on the Virgin Islands. Somewhere in Africa may have been a more appropriate place as we shared so many interests in its arts. We soon became aware that we did not only share interests but that we were also on the same wavelength when it came to the interpretation of what we had witnessed in different parts of the continent. It was the beginning of a long, sometimes interrupted, but never-ending conversation. Sometimes, we met at conferences and also in our homes, but more often, we used all sorts of media that allowed us to keep in touch, as we were both regularly in remote parts of the continent. I believe, this long conversation was what characterized our friendship.

It touched on many aspects of African art, but there were a few central themes that emerged soon after we had met in the Caribbean. Sidney insisted repeatedly on not sub-dividing African art in a “traditional” – or a “historical”, as she later said – branch on the one hand and a “modern” or “contemporary” one on the other. That would, she said, eventually reproduce Western presumptions about art and how it is created. Neither are modern artists as autonomous as the Western artworld imagines them to be nor are artists working in “traditional” settings only bound to old, given styles and iconographies. The continuum of the arts of the continent would make it impossible to work only on one of these constructed realms – a claim with immediate consequences for empirical research. One should have some experience with both, she said. Else one would not understand artistic creativity in Africa, how it had changed in the past and continues to change today. Her poignant critique of the “one tribe – one style” paradigm, which had dominated African art studies for such a long time, grew out of her life and work which lingered repeatedly between modern and historic, but also urban and rural life-worlds. The rejection of these terms as incompatible dichotomies was the basis of her approach – and again something we shared.

Sidney mentioned repeatedly that her contributions to this and a couple of other key debates in African art studies were not well perceived in the beginning. She once mentioned, that the editors of African Arts “didn’t like” her article on authenticity – a text that was later reprinted in prestigious volumes about contemporary arts and their relationship to globalization. It remains certainly one of the most influential in the field. Sidney had anticipated and instigated debates that became central to African art studies.

Publishing together with Sidney was part of this exchange, a sort of ongoing conversation that sedimented in a text that we finally published as a book with contributions from younger scholars. Many of them were former PhD students of ours. Sidney enjoyed how they were engaging with strands of reflection that could be traced back to her early career when she was not yet an eminent professor at Emory University. Weaving these strands together was a big pleasure for her.

It is sad that this conversation, which reflected so many important dimensions of African art, has come to an end. But in my mind, I will continue to exchange ideas with Sidney – and I know, I’m not the only one.

In Memoriam: Daniel P. Biebuyck (1925-2019)

World-renowned Anthropologist, died on December 31, 2019. He was born in Belgium in 1925, and died in Newton, Massachusetts at the age of 94. After studying classical philology and law at the University of Ghent (Belgium), he specialized in cultural anthropology at the London School of Economics. He went on to conduct fieldwork in the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1949-1961. Daniel then relocated to the United States, where he became a professor of Anthropology in several American universities, notably the University of Delaware and UCLA. His pioneering research made him the leading authority on the cultural traditions of the Bembe, Lega, and Nyanga social groups. Among his many publications in English, French, and Dutch, two of his most-acclaimed are: The Mwindo Epic (1969) and Lega Culture (1973). He was the recipient of numerous honors, grants, and fellowships, including the Rockefeller Foundation Humanities Fellowship, the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship, and the National Endowment for the Humanities. In 1989, he retired from the University of Delaware as H. Rodney Sharp Professor of Anthropology and the Humanities.

In Memoriam: David Nthubu Koloane (1938-2019)

by Fiona Siegenthaler

We are deeply saddened by the passing of Dr. David Koloane at his home on 30 June 2019. His rich, inspiring and deep commitment to life, art, and collaborative work has left an enormous imprint on what South African art is today. The development of a black art community during apartheid in South Africa, and the visibility of black South African art internationally in the years of transition cannot be imagined without his enormous contribution. While consistently developing his own artwork over more than five decades, Koloane created space for collaborative art practice, facilitated various formats of art education, mentored the young artist generations while grooming their historical foundations, mediated between diverse constituencies, and curated for local and international audiences.

My first encounter with Koloane took place in 2006 when I visited him in his studio at the Bag Factory where I hoped to learn a bit more about his personal narratives of Johannesburg – in addition to the complex and ambiguous relationship to this town so powerfully reflected in his paintings and drawings. I was overwhelmed by the open arms and spirit of David, the patience with which he described – not for the first time – the living conditions and the disparity between city center, Alexandra and Soweto at the time of his childhood, youth and adult age. It is this enormous generosity with time and attentive patience that made him the person he was – focused and tolerant, engaged and human, and an excellent observer and mediator.

Born in Alexandra in 1938, Koloane experienced Johannesburg as a city of racial and racist division and his own family was not spared from forced removal and economic distress caused by apartheid politics. On the other hand – or just for this reason – he never gave up in his endeavor to create space for black creation and art practice, and for the encounter and exchange of artists and intellectuals. His introduction to the Polly Street Art Center by his classmate Louis Maqhubela and later his involvement in the Johannesburg Art Foundation run by Bill Ainslie therefore were not just the beginning of his career as an artist, but also a spark for creating a spirit of collaborative artistic exchange that challenged racial limitations dictated by apartheid. Koloane later became the director of the first gallery dedicated to black artists and in 1978 acted as the first curator at the Federated Union of Black Artists (FUBA), an outstanding collective initiative of artists, writers and musicians at a time of entrenched apartheid politics. In 1985, he co-founded with Bill Ainslie and Kagiso Pat Mautloa the Thupelo workshops which offered two-week retreats outside the city and which proved crucial as a space to test experimental art practices. Together with Robert Loder, he founded the Fordsburg Artists’ Studios in 1991, popularly known as the Bag Factory, a cooperative space that continues to be a crucial institution on the South African art map. It has been welcoming artists from diverse racial, national and educational backgrounds since its beginnings at the dawn of democracy. Koloane could be found there during weekdays, along with his long-time studio mates Pat Mautloa and Sam Nhlengethwa and the many other artists who worked and continue to work there for shorter and longer periods of time.

Koloane’s sensibility for the power relations inherent in spatial organization was fundamental for all his cultural initiatives which were path-breaking in creating space and public attention for art by black artists. The David Koloane Award and the David Koloane Mentorship Programme offered by the Bag Factory are reflective of this engagement and Koloane’s passion in mentoring and teaching younger generations. As a curator, he cooperated with international colleagues in seminal exhibitions like Art from South Africa at the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford (1990) or Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa at the Whitechapel Gallery in London (1995). As an author of numerous articles about black South African art history and art practice in key publications, Koloane confidently conscientized his audiences for the structural violence put on black creative work. He thereby always emphasized dialogue and conversation as a means of creating connections between people. The appreciation for his scholarly and educational efforts are reflected in the honorary doctorates he was awarded from Wits University in 2012 and from Rhodes University in 2015.

It is comforting to know that only weeks before his passing, David Koloane attended the opening of his retrospective exhibition, A Resilient Visionary: Poetic Expressions of David Koloane curated by Thembinkosi Goniwe at the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town. It is an acknowledgement of his enormous contribution as an artist, curator, teacher, mentor and activist to South African art and its appreciation locally and internationally.

Our sincere condolences go to his wife Monica, his family and friends. May David Koloane rest in peace after a rich, fulfilled and meaningful life, bequeathing an invaluable legacy of artistic mastery and cultural commitment to South Africa’s art world and beyond.

Tribute to Professor Christopher Damon Roy (1947-2019)

by Cory Gundlach

A great tree has fallen (Akan proverb)

Today we mourn the loss of an extraordinary man. Professor Christopher Damon Roy passed away early on the morning of Sunday, February 10 in Iowa City, surrounded by his immediate family. Chris was born September 30, 1947, in Ogdensburg, New York, to Margaret Adam Snow and George Robert Roy. He and his wife, Nora Leonard Roy, were married at the Hôtel de Ville, Ouagadougou, Upper Volta, on September 26, 1970. He leaves his beloved wife, Nora; his son, Nicholas Spencer Roy (Jill Scott); his daughter, Megan Deirdre Roy (John Dolci), and granddaughter, Sylvia Elizabeth Dolci; his sister, Robin Roy Katz (Michael Katz) and nephew Teddy Katz; his brother, Matthew Roy (Caroline Darlington Roy); nieces Katelin and Emily, and nephews Robby and Chris. Those close to Chris will remember him well for his sincere warmth, delightful wit, and bold sense of humor. Always approaching life with a sense of adventure, his robust energy and fascination with the world was contagious during his forty-one years at the University of Iowa.

Throughout his career, Chris devoted much of his attention to the arts of Burkina Faso and the Max and Betty Stanley Collection of African art. His writing on the Thomas G.B. Wheelock Collection is well known, and many will remember him for his catalog on the Bareiss Family Collection. Over the years, he contributed regularly to African Arts, where he published on his research in Burkina, reviewed exhibitions, and engaged in current debates. His 1980 review of Traditional Sculpture from Upper Volta remains one of the sharpest critiques in the field. In 2015, he published his most recent book, Mossi: Diversity in the Art of a West African People,as well as an essay, “The Art Market in Burkina Faso: A Personal Recollection,” included in Silvia Forni and Christopher Steiner’s Africa in the Market: Twentieth-Century Art from the Amrad Collection. His Art of the Upper Volta Rivers (1987) remains a standard text on the subject.

In addition to this, Chris produced over twenty self-narrated video recordings on the arts of Africa, and all are freely accessibly online. He and Linda McIntyre released Art & Life in Africa (ALA) as a CD-ROM in 1997 and sold thousands of copies throughout North America. In 2014, he worked with Dr. Catherine Hale and Cory Gundlach to redevelop ALA as a website, which has had nearly 500,000 users. As a leader in his field, Chris founded and directed the UI Project for Advanced Study of Art and Life in Africa (PASALA), which provided scholarships for graduate course work and research in Africa, as well as conferences and publications on African art.

Chris’s impact as a professor was no less remarkable. Every fall semester, twice a week, nearly 300 students packed the largest lecture hall at Art Building West to attend his survey course on African art. High enrollment was common for his all courses, as he was a gifted storyteller and he understood the power of keeping his students entertained with occasional humor. A long history of work with the Stanley Museum of Art supported his object-oriented approach to teaching, which he complemented with a social history of art. He oversaw the completion of fifteen doctoral dissertations, and many of his former students are now employed in major institutions throughout the country.

From 1985 to 1995 at the Stanley Museum of Art, Chris served as curator of the arts of Africa, the Pacific, and Pre-Columbian America. He curated fourteen exhibitions during his university career among museums in Iowa, China, Austria, and Germany. Scholars reviewed his exhibitions at the Stanley Museum positively for the way in which artistic quality drove his motivations for selection and display, and for the way in which he treated attribution carefully.

Beyond his scholarship, teaching, multi-media projects and exhibitions, Chris’s YouTube videos on art and life in Africa have reached perhaps the widest audience, with more than 10,000 subscribers and over four million viewers worldwide. It is encouraging to think that the world is a better place because of Chris and all of those touched by his warmth and brilliance.

In Memoriam: Marilyn Eiseman Heldman (1935-2019)

by Jacopo Gnisci and Peri Klemm

The loss of Marilyn Eiseman Heldman (June 12, 1935 – July 15, 2019) marks the passing of a brilliant scholar and generous colleague who pioneered the study of Ethiopian art. Her work on the illustrated manuscripts and devotional icons of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church examined issues of patronage, spirituality and inspiration.

Her 1972 PhD thesis on the Miniatures of the Gospels of Princess Zir Gānēlā, an Ethiopic Manuscript Dated A.D. 1400/01, is, to this day, the only work which provides an overview of all the illustrated features of medieval Ethiopic Gospel books. Covering a wide range of visual evidence, the study traces the pictorial sources and religious practices which shaped the work of Ethiopian illuminators active towards the turn of the fifteenth century. She was among the first art historians to study historical devotional Ethiopian artworks with this kind of depth.

In her book, The Marian Icons of the Painter Frē Ṣeyon: A Study in Fifteenth-century Ethiopian Art, Patronage, and Spirituality, Heldman begins with a single work of art as a window into the religious paintings traditions of the mid 1400’s. Frē Ṣeyon, a monk from the monastery of Dabra Gwegweben, signed only one painting, but by comparing stylistic and iconographical characteristics to other mural and panel paintings, Heldman was able to assign an entire oeuvre of painting to this monk and to identify the Byzantine and Italian prototypes.

Heldman was also much involved in the organization and catalogue of the exhibition African Zion: The Sacred Art of Ethiopia (1993). This landmark exhibition, which brought Ethiopian art to the attention of the American public, remains unsurpassed. The art historical essays in the catalogue, written by Heldman, combine clarity with academic rigour. It is also worth remembering that Heldman, in the second of her five essays in this volume, was the first scholar to suggest, on stylistic grounds, that the Garima Gospels were produced during late antiquity, a hypothesis that would be later confirmed by C-14 dating.

In Memoriam: Marshall Ward Mount (1927-2018)

by Perrin Lathrop (PhD Candidate, Princeton University)

I learned of Marshall Ward Mount’s November 25, 2018 passing from my aunt this past January. A Jersey City native, like Marshall, she had been thrilled by my first visit to the storied Mount home more than twelve years ago. The opportunity to view the African art collection he had amassed over decades of research travel to the continent made a lasting impression. While enrolled in Professor Mount’s Arts of Africa course as an undergraduate at New York University, I, along with hundreds of students from Marshall’s six decades of teaching, was exposed to the history of African art for the first time. His passion and enthusiasm for the subject impressed me. His personal attachments to the objects, to their lives and stories intrigued me. The box of Paul Wingert’s African art prints that I purchased for the class still sits on my bookshelf – a reminder of my introduction to a canon of objects that I’ve since learned to deconstruct, complicate and expand. Some of that crucial work began by later reading Marshall’s own book, African Art: The Years Since 1920 (1973), the research for which he received a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship as a student of Paul Wingert’s at Columbia University. This book is integral to the historiography of modern and contemporary African art history. With a generous and encouraging spirit, Marshall eagerly supported me in the early stages of my career. He introduced me to individuals whose own generosity made the pursuit of a life in art history seem possible. As I look back through my correspondence with Marshall, I am reminded of just how significant his support was to my own growth in this field. I visited Marshall and his wife Caroline’s Jersey City home for a second time while research assistant for the Arts of Africa collection at the Newark Museum. Beyond the thrill of viewing his collection with more discerning eyes, I remember Marshall’s stories. In one, he joyfully recounted his return from one of his first trips to the African continent. With a twinkle of mischief in his eye, he recalled the moth infestation that took hold in his mother’s home when he opened the crates of art and textiles he brought back from his trip, an inevitable inconvenience of the journey. Through his collecting and teaching, Marshall allowed me, and so many others, to witness firsthand the ways African objects and narratives have been mobilized to take root in the cultural imagination, both far and very near. He brought African art “home” for me as a fellow New Jerseyan and opened my eyes to the world right outside my door. Donations may be made in Marshall Ward Mount’s memory to the African Wildlife Fund.

In Memoriam: Bisi Silva (1962-2019)

by Peju Layiwola (ACASA Board President Elect / VP)

It is difficult to speak about Bisi in the past tense! Bisi Silva was born in Lagos in 1962 and died on the 12 of February, 2019. She was the founder and artistic director of the Centre for Contemporary Arts, Lagos established in 2007. In the 11 years of its existence, her Centre became ‘the’ Centre of art in Nigeria. Bisi centred the discourse on contemporary African art on the continent and brought several international scholars, artists and curators to Nigeria. Her Centre became a gateway for establishing connections between local artists and international audiences. It brought joy, laughter and professional fulfilment to many. Bisi lived a short but purposeful life. She brought to the art scene a high-level of professionalism and impacted both young and old artists through her unique exhibitions and artists talks/programmes. She was a scholar and curator extraordinaire and internationally recognised for her immense contribution to art scholarship. She developed the art of photography, video art and other aspects of new media which were largely underserved in Nigeria at the time.

She transformed the careers of a good number of artists and curators from all over the world. She will be fondly remembered for the Asiko curatorial school. At home, Bisi made it possible for young art graduates to think of establishing careers as curators. She supported several art programmes in different parts of Nigeria and endowed prizes for the best entries in the arts at national competitions. She made donations to many art programmes and projects. Bisi curated several local and international exhibitions and biennales, too numerous to mention here.